The Last Apples of Kazakhstan: Modernity, Geo-Politics and Globalization in Central Asia

Collaborators: Manu P. Sobti

"Ten years ago I should have said that any fuss about food was too great, but I grow older and food has become more important to me … Judging from the space given to it in the media, the great number of cookbooks and restaurant guides published annually, the conversations of friends - it is very nearly topic number one. Restaurants today are talked about with the kind of excitement that ten years ago was expended on movies. Kitchen technology – blenders, grinders, vegetable steamers, microwave ovens, and the rest – arouses something akin to the interest once reserved for cars … The time may be exactly right to hit the best seller lists with a killer who disposes his victims in a Cuisinart."

(J. Epstein, Aristides, Foodstuffs and Nonsense, 1978, pp. 157 – 58.)

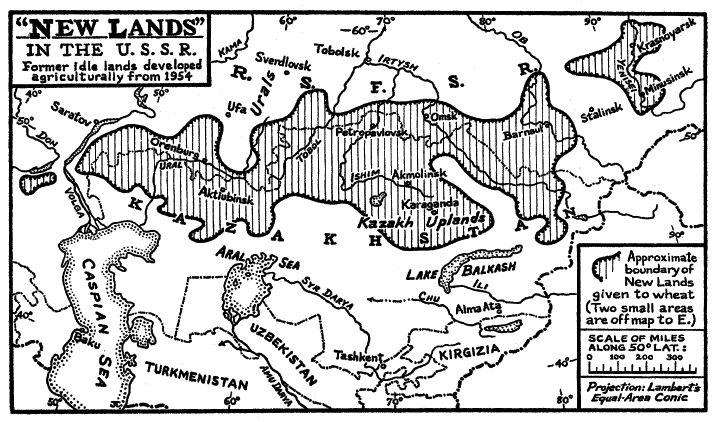

Kazakhstan as “Russia’s Agricultural Crutch”, 1950 - 70

In the future worlds of the so-called ‘Food Inc’ and the ‘New Gene Café’ the most pressing concern for all is assumed to be the quality of the stuff on our plate. Exactly how and why GE foods impact our bodies in a diversity of ways is no small matter. However, since Epstein’s writing in 1978 (as quoted above) on the probable killer of future lore – and one exceptionally well-versed in the production of delectable culinary arts via its occupational tools – food has become even more important to everyone. More insidious now is the implication of how the grandiose ‘Food Inc’ in its multiple avatars of accidental versus selective breeding (and un-breeding), in other words the politics of its ‘production’, may potentially dismantle entire cultures, local histories and spatial patterns. This myriad of changing scenarios and their brutal assault on the means of production are indeed bound up with the negation of consumption ethics that undermine the historical and cultural dimensions of diverse global populations. Their traditions and performative practices still remain bound with the foods they have traditionally grown and continue to consume. In effect, not only have we as a global collective grudgingly reinforced views on how the consumption of foods (or the lack thereof) can kill via the mundane bodily processes of gluttony and decay; but we have also discovered how in the very production of this food (including the killer’s preoccupations with Cuisinart’s nuances to perfectly mince and dice), could irreversibly change those who prepare this spread. Within Levitt’s broad trope of globalization and its scenario of wider markets, therefore, food has become critical to those who consume it and produce it through means both natural and man-made.

This research project examines critical assessments on why the survival and preservation of ‘native’ food species is indeed critical to cultural-historical diversities of the places these emerge from. The means and modes of production, normatively applied to genetically altered, quasi-artificial, and factory-orchestrated combination foodstuffs (including TV dinners, instant foods and so forth), is now extended to include the seldom-researched, yet complex social scenarios that presage the survival or disappearance of ‘native’ species. Not all foodstuffs are grown; some are benevolently allowed to prosper within their geographical settings. Discerning where a crop or food-stuff originated and where the greatest portion of its genetic diversity remains extant may seem esoteric to the uninitiated, but knowing where exactly our food comes from - geographically, culturally, and genetically – is of paramount importance to the portion of our own species that regularly concerns itself with issues of food security. Within this complex purview, three questions are addressed. At a first level, how must genetic specificities (and consequently genetic diversities) be preserved in this climate of unprecedented global change where commercial conveniences often trump local ones? Is genetic specificity indeed a realistic expectation? Secondly, how shall the loss of genetic specificity among foodstuffs expedite the loss of culture and place? This goes back to our contention that while foods (including crops and fruits) may originate by chance, their survival depends on conscious intention. Thirdly, how do bio-diversity hot spots map on to cultural diversity hot spots at the global scale? In other words, maybe stories of “mother” species should cross beyond the traditional disciplinary parameters we often set for ourselves.