This website has been tested on Firefox and Chrome. Currently, content is best displayed on 900p monitors and higher (all modern screens meet this requirement). Contact jonus.darr@uqconnect.edu.au for academic or technical issues.

DISCONNECTED SOCIETIES IN A CONNECTED LANDSCAPE

Examining Yemen’s societal disharmony through the people of the Sana’a Basin’s management of water and their response to flood disaster.

Thesis by Jonus Darr in partial completion of the University of Queensland's 'Master of Architecture' program.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Ronald Lewcock and Michele Lamprakos for your publications and responding to my queries.

Thank you to the UQ School of Architecture and the ARMUS library for your assistance and the resources provided.

Preface

As of 2017, approximately three quarters of the twenty-six million people living in Yemen do not have access to clean drinking water. While the floodwaters which descend the country’s geography once supported the long-standing populations of the Sana’a Basin, today, the city of Sana’a is instead battered by these floods. Even more dire is the limited access Yemenis have to water, which is claiming thousands of lives and continues to cripple the wealth of what is already the poorest country in the middle-east. The staggering deaths and loss of wealth is rather contrary to historical depictions of Yemen, when organisation and ingenuity prevailed, and the dense populations of pre-modern Yemen prospered despite the arid climate.

Commentators from many different backgrounds assert varied causes of Yemen’s water management problems. The Guardian paraphrases Ghassan Madieh (former water sanitation and hygiene specialist for UNICEF in Yemen) who criticises the government for their lack of funding, poor governance, and its failure to provide adequate support for water projects,2 while, USAid’s Craig Giesecke claims that water scarcity is actually contributing to the country’s political, social and economic instability.3 In a Time Magazine interview, Michael Klingler (hydrologist and local director for the German Technical Coorperation Agency) focuses on the traditions of the Yemen people rather than the inefficiencies of the state, noting that 30% of the country’s water is used to irrigate qat, a narcotic stimulant used ritually by most Yemenis.4 These and the countless other valid claims and accusations do not override one another, but rather correlate to depict the thematically entangled problem of water mismanagement in Yemen. Through the interrogation and cross-analysis of papers, interviews, reports, masterplans, geographical maps and meteorological data it has been revealed that all of the causal interrelating topics of water mismanagement hold one common theme — societal disharmony. Focused on geography, society and history, this research firstly traces the schismatic effect of rapid modernisation on the ancient people of the Sana’a Basin, and then focuses to describe the effects of this unbridled modernisation on water management.

Contents

Click on text to jump to section...

1.0: Research methodology and perspective of the Sana'a Basin

1.1: Approach 1: The creation and analysis of hydro-maps

1.2: Approach 2: Dialectical analysis of interdependent people systems

1.3: Approach 3: Applying the dimension of time to the previous two approaches

2.0: Historical and geographical backdrop of the Sana'a Basin

2.1 Geographical backdrop of vernacular development

2.2 Tracking the premises of the 1962 revolution

3.0 The 1962 revolution as creating a schism between the 'worlds of old and new'

3.1 The three dialectics of this schism.

4.1 Case study 1: Capitalism, irrigation, agriculture and qat

4.2 Case study 2: Hybrid urban lifestyles of 'old and new'

4.3 Case study 3: Shifting approaches to conservation on the Wadi al Sailah

4.4 Case study 4: The atomistic modern development and its contributions to water mismanagement.

4.5 Case study 5: Informal developments of the Wadi al Sailah

5.0 Summarising the phenomena of atomistic societies’ water mismanagement and the ramifications.

6.0 Endnotes.

1.0: Research methodology and perspective of the Sana'a Basin

Figure 2: Argument as a section through all three approaches5

The multifaceted approach adopted in this research endeavours to pivot the understanding of Yemen’s hydrology/topography, the people and their developments co-existing as one system. The element of water is central to this system; it has flowed through Yemen’s landscapes for thousands of years, conditioning vernacular developments and the local inhabitants within a harmonious cycle. This harmony incorporated all the roles which the element of water has played through time, as an asset, a resource, a basic human need, a danger in the form of flood, and as a ‘land-form’ of sorts. While the pre-modern societies of Yemen had always been ‘aggregated’, they wouldn’t be considered ‘atomistic’, as for thousands of years they shared a common doctrine of universal water management practices and laws. The complexities of modernisation have atomised and removed the harmony of these aggregates, and in addition to clashing societal hierarchies including the introduction of a centralised state, the now atomistic societies struggle in disharmony. Understanding this change requires an understanding of how the aforementioned cyclic influences between people, their built environments and the landscapes they inhabit change throughout time.

- Hydro-mapping of the region’s landscapes and built environments to gain spatial understandings of the people’s relationships with water via their developments.

- Societal relationships, hierarchies and divisions recognised as stemming from a series of dialectics; global versus local, modernity versus tradition and, centralisation versus aggregation.

- Timeline analyses so that change between the inter-influencing topics of society, development and landscape can be understood.

1.1: Approach 1: The creation and analysis of 'hydro-maps'

The creation of ‘hydro-maps’ is a method whereby people’s relationship to water is investigated via the interfaces between their developments, and the hydrology of the landscapes they inhabit. These maps correlate and collate a variety of water infrastructure types, urban patterns, and land-forms. They are therefore a tool for investigation, and while they are often created to test an assumption they have also provided new insights. For the case of the Sana’a Basin hydro-maps are used to analyse how the sustainability of pre-modern Sana’a was achieved. In contrast to the sustainable systems of pre-modern Sana’a, other hydro-maps depict modern development trends and hydro-interfaces that identify the basin’s incohesive and fragmented urban forms. The maps of pre-modern and modern Sana’a are compared for context, and to identify water management related incompatibilities.

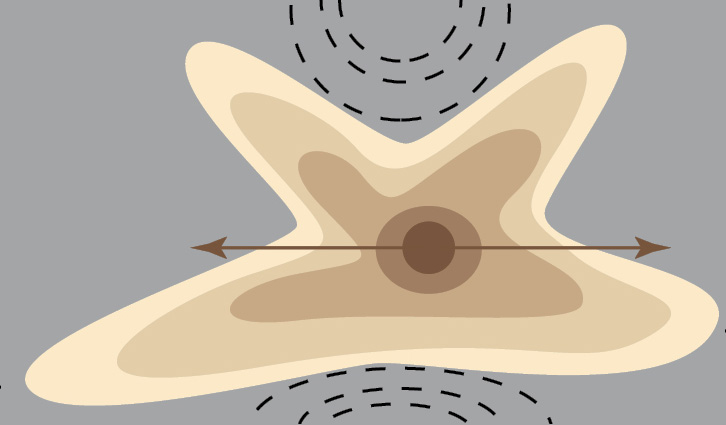

The Sana’a Basin is located in the north-west of Yemen in between Mt. Nuqum and Mt. Ayban mountains in the Sarawat mountain range. Yemen owes its reputation as being dubbed Arabia Felix (Latin for fertile, happy and blessed Arabia) to this mountain range as its landscapes are characterised by several highland basins (refer figure 1) which are rich in alluvial soils and sub-soil aquifers. A basin-wide geographical analysis of pre-modern development locations, water paths and alluvial silts reveal the fractal-like nature of the landscapes in the Sana’a Basin and a resulting aggregated pattern of development (refer figure 3). The recursive fractal pattern of ephemeral rivers is comparable to a tree, whereby smaller tributaries from the mountains are like stems feeding into larger ones until they all eventually converge at the thick trunk - the Wadi al Sailah. This main ‘vessel’ of the catchment is where the basin’s largest settlement is located - the city of Sana’a. Higher amounts of floodwater and the abundance of alluvial soil predestined Sana’a’s predominance as a major city over the surrounding villages. This reasoned genesis and destiny of Sana’a is one example of how patterned spatial and societal generalities for the entire region could be identified, thereby providing a logical framework towards investigating specific case studies. Conversely, the discussed specifics of societies, vernacular developments, civic infrastructure, state infrastructure, cultural places of significance, and agricultural lands are correlated to exhibit broad patterns and generalities. While being factual as possible to address the topic with substantial information, the reductionist nature of such analyses is that the unique components of each and every aggregate cannot be proven as contributing to a broader system. Similarly, nor can each and every aggregate be proven as part of an apparent system assumed by the generalist ‘logical framework’ formulated. Considering the Sana’a-city-scale, Elsheshtawy acknowledges the balance of uniqueness and sameness found throughout the region in his description of the urban fabric and the architecture of the city’s towerhouses:

“The urban pattern of the city comprises many housing clusters that are similar in the orientation and spatial organization of their elements, but different in shape and size. It follows a hierarchical system of organization that seemed to be very efficient in providing appropriate functional spaces for both public and private zones and the required separation between them.”6

These and other recognised generalities form an understanding of pre-modern Sana’a, and provide a framework for such analysis. While these patterns themselves are worthy of analysis, it is the fracturing of these urban patterns which may signify a disjointed approach to water management. These disjointed patterns are generally seen in modern Sana’a, which does not conform to, or successfully integrate with a pre-modern pattern, nor has modern Sana’a formed its own cohesive urban pattern.

Figure 3: The multiplicity of villages in the Sana’a Basin indicate the city’s genesis 7 - 10 000m grid

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Map Description:

For an area of approximately 36 000 hectares, the Sana’a Basin contains a relatively small variety of landforms which form in patterns across the region to create an equally and somewhat evenly dispersed set of landscapes. Mountainous terrain girt the region closely to the east and west, and, distantly to the south. Water run-off from these sandstone and volcanic mountains carry silt down the wadis (ephemeral rivers) which appear radially from the centre of the basin, forming a large floodplain. While Abuel-Lohom and Gad accurately depict the catchment leading water from the entire basin to a single natural outlet in the north,8 it appears water rarely leaves the basin as the alluvial floodplain (and therefore the flood water which carries its silt) stops over 10 kilometres short of the northern low point.9 This is probably due to the massiveness of the floodplain, where the run-off water is usually absorbed into a large underground aquifer on which Sana’a is founded.10 The weak alluvial soils are easily dug into wells and provide much of the arable soil in the region. These patterned geographies are therefore the generators of the patterned placement of settlements throughout the basin.

1.2: Approach 2: Dialectical analysis of interdependent people systems

After the dethroning of the Imamate in 1962 the city of Sana’a was founded as the capital of the newly formed North Yemen Republic. The country proceeded to override and reform its traditional policies and laws regarding land tenure, agricultural practice, trade and water management. People began to flock to the city for the work opportunities presented in new industries and services as well as for the access to these products/services (such as roads, hospitals, running water, sewerage). Rather than stabilise, the city’s importance boomed once more in 1994 at the end of a brief war between the North Yemen Republic and the The People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen as it became the capital of the unified Republic of Yemen. And so the population of the city continued to skyrocket, while before the unification of North Yemen and South Yemen the population had already doubled from 427 505 in 1986 to 973 548 in 1994, it was set to almost double again reaching 1 747 627 only 10 years later in 2004 (refer to figure 5).11 These massive shifts in demographics and the lifestyles of the Yemeni population would not have happened if it wasn’t for the revolution of 1962, and, given the current dire state of the country it is fair to say that this revolution is a kind of pivot between the sustainable pre-modern Sana’a an and the unsustainable modern Sana’a.

Many of the clashing societal and water management topics resound this claim that the 1962 revolution allowed for the rapid and unguided globalisation, modernisation and centralisation to impede on the local, traditional and aggregated societies of the Sana’a Basin.

The schism within Yemeni society as identified by these three dialectics — global versus local, modernity versus tradition and centralisation versus aggregation — is proven by investigations which reveal divisions in water management strategies, society, culture, politics, agricultural practices, services and infrastructure planning. By correlating and collating sections of this catalogue (refer to figure 4), the general arguments and specific case studies which compose the following sections of this thesis were formed. Furthermore, in curating these arguments with this diagram and the other two approaches care has been taken in order to not sever the topics (or relationships of) of most importance from the limited scope of this thesis.

Figure 4: Adjacencies of interdependent people systems 12

1.3: Approach 3: Applying the dimension of time to the previous two approaches

Figure 5: Time-line of Sana’a and its relevant contexts13

All the rigid findings of societal relationships over the Sana’a Basin are projected throughout time. Time contributes a fluid understanding of how societies evolve alongside their manicured landscapes. Examples of pivotal moments in a society’s history (for example, the revolution of 1962) or flood events are analysed beyond the point of before and after. The accumulating negative effects of these events are therefore measured and correlated.

In relation to approach 2, an investigation of the region’s longstanding history discerned as to why Sana’a could not integrate the rapid changes of modernism and modern development successfully. Millenia of traditional aggregated and in many ways even tribal societal systems/hierarchies had evolved alongside their geographies maintaining a sustainable and harmonious existence. Due to the interdependencies between their practices, beliefs, cultures and geographies, changes to any of these components jeopardise the entire system, and so these changes are resisted even to this day.

2.0 Historical and geographical backdrop of the Sana’a Basin

This section views Sana’a’s societal and political history, especially in the decades leading up to the revolution in 1962 as partially determined by the patterned nature of the arid landscape. In section 2.1, vernacular design, landscape/hydrology and traditional social practices/laws have been realised as components of a greater interdependent system. In section 2.2, this rigid and interdependent system, which was conserved for hundreds of years in an increasingly liberal world, has been found to be a kind of premise to the 1962 revolution.

2.1 Geographical backdrop of vernacular development

p>The arid climate of Sana’a receives a petty average of 265mm of rainfall per year, though up to 60mm of this may fall in 24 hours. Additionally, annual rainfall is focused in two short wet seasons whereby approximately two thirds of the average rainfall occurs in the three months of April, July and August. It is common for the region to experience very little rainfall for five months over Summer.14

In order to accommodate these extreme contrasts of flood and drought, the region, just like many other regions in the world, had traditionally devised and evolved practices which capacitate flood water, effectively mitigating floods and drought. Responses to the landscapes’ and the climate’s flooding and drought are evident in the agricultural practices, development patterns and even societal hierarchies of the region. For the vast majority, if not all pre-modern developments in the Sana’a Basin, the ancient urban practices of agriculture on a wadi bed with overlooking flood-resilient towerhouses in between define the basic urban character of the region. Investigations at a finer scale reveal a definitive collection of small scale infrastructures; spate distributing canal systems, dykes, terraces, cisterns, canals from mosques’ ablution baths, wells, and public baths, all of which are functionally arranged/adjacent to intelligently use and re-use what little water falls on the region, examples of these are described and depicted throughout this thesis. Terraces are a notable example of small-scale infrastructures multiplied extensively to mitigate floods and use water very efficiently, their action will be explained further in case study 1. The increased groundwater permeation from the practice of constructing agricultural terraces found on the foothills surrounding the lower basin not only irrigate the crops and recharge the groundwater aquifer but also prevent excess runoff which would otherwise contribute to flooding downstream in the city.15

A feedback loop occurs whereby these small-scale infrastructure systems which contribute to a regional system of water management are both generated from and yet premise components of the region’s traditional political hierarchy. Specifically in the case described by the Food and Agriculture Organization, authorities and their parent hierarchies are appointed and organised (respectively) to manage irrigation disputes and the community’s water supply (refer figure 8):

“In Hadran (in the Directorate of Bani Matar, Sana’a Governorate), Yemen, the grand sheikh (sheikh daman) represents the whole community within official circles, deals with tribal and rangeland disputes at the sub-district level (uz-lah), and is responsible for solving problems at the village level. The rank of the sheikh at the local (uzlat) level comes after that of the grand sheikh. The “wise man” (akel), is found at the third level, tackles land and irrigation disputes, and collects the religious tax (zakat) from the farmers…. The sheiks are responsible for supervising the rangeland activities related to hema, and the mukaddam (guardian, usually the head of an extended family) of the mian (water source), who is selected by farmers, is responsible for distributing irrigation water, and cleaning and maintenance of the irrigation system.”16

This governance hierarchy resultantly effected the physical outcomes of these system’s parent infrastructures, architectures and urban fabrics. These relationships between human needs, social hierarchies and the landscape were in turn influenced by living environments. This is one example of the aforementioned feedback loops whereby society, development and landscape are all interrelated.

Over time, the ongoing influence from these feedback loops created a series of systems with countless dependents (refer figure 9 series). Primarily, this interdependent system of infrastructural patterns, human-networks, customs, laws and manicured hydro-landscapes were the product of the people’s needs to seek shelter, mitigate flood, access water and produce food. In effect, changing landscapes, people, and their development practices were influentially interwoven and/or tangled around human needs (water, food and shelter) as they changed through time. The existence of this composite system is found, in some form at least in all traditional, modern and traditional-modern-hybrid societies, though they each exercise varying levels of success in managing flood, food and water.

Notably, there are also pre-modern examples of large scale infrastructure projects which exhibit a more ambitious and centralised approach to water access and flood mitigation. Even as far back as the 8th century BC, when the region was governed by the ancient Sabeans a massive dam was built 100kms to the east. The Ma’rib Dam was a complex feat of engineering for the time with an earthen bank 600m long, a series of several sluices to control its outlets and overflows, and a distribution tank with many outlets to feed the city of Ma’rib.17 Without this dam which flourished the Sabean empire, Sana’a may not have ever of been founded. The construction of Sana’a’s enormous mud fortification in the 9th century has completely diverted the flood-course of Mt. Nuqum which once ran through the city. Parts of this wall key to mitigating this flood remain after 1200 years (compare figures 9.2 and 9.4).18 There are also pre-modern occurrences where the urban society and the state collaborated on large-scale manifestations of small-scale systems, for example Sulayhid Queen Awra of the 11th century had spent much of the throne’s annual budget on repairing terraces.19

Figure 6: 1946 map of the Old City by the British Navy20

Figure 7: Topical locations of the Old City, Bir al-Zab and in between21

The locations pinned in this map have been referenced throughout the thesis.

Figure 8: Comparison of pre-modern and modern political structures/hierarchies22

Figure 9: Hydro-maps of the Old City - click to scroll through - scale: 200m grid

2.2 Tracking the premises of the 1962 revolution

The aforementioned hierarchical structures of the traditional government system appear soft by today’s standards, in that they delegated powers to the regional tribal authorities so that these leaders could manage themselves and the small scale societal and infrastructural networks as quoted earlier. However, the Imam Yahya Hamid Ed-Din, who was the second last King of the 688-year monarchy of Yemen (excluding the interluding years when the Turks ruled on two occasions), like the Imams before him conserved himself and his system via strident restrictions of, international transport, communication, trade/reform, and the media throughout most of the first half of the 20th century.32 Citizens were effectively isolated from the evolving world as explained in the opening sentences of Burrowes’ paper The Famous Forty and Their Companions:

“To a remarkable degree, Imam Yahya Hamid al-Din of Yemen insulated the traditional Islamic country he ruled from the modern world for a generation – in part, by not allowing his subjects to leave his domain.”33

Al-Abdin further explains the psychology behind the dictator in the following words:

“The colonization of Arab countries by Britain and France and of Abyssinia by Italy was a lesson fresh in Yahya’s mind. Thus, he jealously guarded the sovereignty of his country and its traditional religious way of life by isolating it from foreign influence. He refused to allow in the country diplomatic missions or Western commercial companies or to encourage any form of contact with the outside world. He answered a critic, who pointed out the economic benefits that foreign firms would bring to the country, by saying that they did not help India to avert repeated famines; and that he and his people would rather eat straw than allow foreigners into the Yemen.”34

In the 1940’s the Free Yemeni Movement rose against the monarchy that conserved the aforementioned systems in a rapidly developing world. The people of Yemen learned from the movement’s members who shared their acquired knowledge of the technologies and societies of the outside world, where modern governments and trade reform improved human rights and living conditions.35 Notably, Imam Yahya Hamid ed-Din himself had sent out forty men to several foreign countries throughout the middle-east and even Europe to learn new skills of governance for his restless population, though these men upon their return would actually work towards breaking down the country’s segregation from the global community, contributing to the end of the conservative monarchy.36 A civil war broke out in 1962 against the Imam al-Badr who took the throne that year after Imam ed-Din died in his sleep.37 Militarily supported by the Egyptians whom were well invested in the ideology of Pan-arabism,38 Yemeni rebels would fight the monarchy for eight years of civil war before becoming relatively stable (politically speaking) republic in north Yemen (refer figure 5 for chronology).

Figure 10: Imam Badr was contested since taking the throne in 1962 and was overthrown in 1970 40

Figure 11: Abdullah Al-Salal, leader in the 1962 revolution and first president of Yemen Arab Republic39

Figure 12: Royalists marching along a wadi bed in 196241

3.0: The 1962 revolution as creating a schism between the 'worlds of old and new'

The resultant republican government has since struggled to assimilate the long standing ‘bottom-up’ hierarchical structures of the aggregated societies with its centralised ‘top-down’ methods of management and decision making. An increasingly polarised schism occurs whereby independent local societies resist the changes of government and retain their independence by not paying diligence to centrally decreed planning policy and water management practices/restrictions. In his A Political History of Civil-Military Relations in Yemen, Fattah relates Yemen’s current civil war with broader historical phenomena of decentralised Yemeni forces, which, in turn create stronger local, albeit divided communities:

The onset, escalation and de-escalation of the long post-revolution civil war (1962-70) determined that modern Yemen would be a tribal republic. The incubator of such a republic, known as the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR), is Yemen’s domestic political arena, which is dominated by powerful tribal leaders, and an arrested state. The latter refers to a state that is severely limited in terms of its ability to exercise power and authority. According to Burrowes, this condition of arrested statehood in Yemen is both “cause and effect of the predominantly tribal-military regime that remains firmly in place today…… From the beginning of the republican revolution (1962), it was clear that the military was weak and disorganized, and that there is a wide gap between the political ideas espoused by the republican officers and the particularities of Yemen’s society, which is fiercely tribal, decentralized and deeply steeped in tradition.”42

The effects of modernism, including the inefficient governance of the newfound arrested state, the extreme population growth of the past five decades and the introduction of modern technology all completely reshaped the once organised and aggregated societies’ water management strategies, agricultural practices and development patterns into ones that are now, unsustainable. Calls for change by the inadequate government to the practices of these now divided traditional-modern-hybrid or quasi-vernacular societies became more drastic as the effects of their bad practices worsened, and these societies tended to meet these louder calls with further resistance (refer to quote in endnote).43 The inadequate ill-equipped (in terms of policy, resources and enforcement) state allows but also fails to regulate the Yemeni population’s private, fragmented and incohesive developments of the 20th and 21st century. Elsheshtawy, an expert of masterplanning in Sana’a describes the haphazard urban fabric of Sana’a:

It is very difficult to recognize dominant or consistent urban patterns in the architecture of the new areas of Sana’a. The layouts in the new districts are so varied and often do not follow any urban rules or standards. The absence of any policy with regard to city planning and building codes, the lack of urban planning experts, and the lack of control over the widespread construction of housing have been the major causes of the existing lack of uniformity.44

Exacerbated by Yemeni’s isolation, and the existing aggregation of Yemeni societies, the rapid onset of modernity (in its broadest definition) on a rigid and in many ways resistant traditional population has produced an increasingly polarised schism between the worlds of ‘old and new’. Within this schism is the re-ordering of political hierarchies, which has fractured traditional Yemen societies, causing them to atomise when previously they would have been described as aggregated.

3.1: The three dialectics of the schism

Following the 1962 revolution, the rapid onset of globalism, modernism and the resultant centralisation in the capital of Sana’a clearly opposed its rigid aggregated network of traditional societies, in turn a set of dialectics between the lingering old and the surging new polarised one another. Between the worlds of the old and new, contrasting controls and strategies clashing in policies and infrastructures have led to inefficient water management amongst other problems. In this regard, pre-modern Sana’a is acknowledged for its sustainability, evidenced by the systems described in part 2.1 and figures 8, 9, 18, 19 and 20, as well as the fact it remains as one of the oldest inhabited cities in the world. While the benefits of globalism and modernism shouldn’t be discounted, it is evident that Yemen’s problems of sustainability come from the rapidity of revolutionary globalism, modernity, centralisation and the clash of these changes with the people of Sana’a’s rigid and ancient societal and urban frameworks. In essence while the aspects of the ‘new’ Yemen failed to consider and integrate its historical context, the rigid historical frameworks proved somewhat inflexible at effectively integrating the positive changes of modernisation. The dialectic components of this schism are evidenced by the topics of infrastructure, society, politics, ideology, and planning/policy.

4.1: Case Study 1: Capitalism, irrigation, agriculture and qat

As identified through the previous sections of the thesis, vernacular patterns of agriculture serve as a major determinant shaping societal hierarchies and development patterns. This case study investigates the distinction between ideologies of the old and the new, the unsustainable old-new hybridisation of agricultural practices, and the modern phenomena of rural-urban migration as problematically cumulative, causing unsustainable environmental change, starvation and dehydration.

Lichtenthäeler describes that between the country’s constitution’s reference to Islamic law and the state’s claim to ownership of natural water bodies there resides a logical flaw:

“According to the constitution of Yemen, the sharia is the basis of all legislation... According to the sharia, water cannot be possessed by anybody unless it is contained. In contrast, the constitution states in article 7, that water belongs to the state: “All natural resources [...] whether above ground, underground, or in the territorial waters are owned by the government which will ensure exploitation of such resources for the common good.”45

Such a flaw within the country’s own constitution is great testament to the argument that many of the region’s water management related problems are the state’s failure to integrate its governance onto a resilient and orthodox society with firm roots in traditional law (‘urf) and religious law (sharia). Water rights/policies outside of traditional laws (‘urfs and sharia) which restrict or even meter water has been met with disregard, contempt and suspicion by the local farmers.46 The Yemen Times have reported cases of armed resistance against the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation during their attempts to undertake water management projects on agricultural land.47 Because of the arrested state causing situations like these, 99% of groundwater extraction in Sana’a still remains unlicensed.48

Hybridised old and new agricultural practices are unsustainable and damaging to the welfare of Yemen. Specifically in the following argument, the adoption of modern technology and the capitalist economy versus the retaining of traditional agricultural law is proven to be extremely detrimental to food production and water access. The economically efficient use of mechanical pumps to over-exploit evermore deepening wells has contributed to the reduced area of rain fed agriculture compared to total cultivated land from 85% in 1972 to 59% in 1988.49 Veranda Fernando states the perceived inefficiency of traditional rainfed terraced farming:

“The size of each individual terrace varies but is seldom large enough to allow proper utilization of standard agricultural machinery. On the contrary, the terraces are often so narrow and located in such a way that the obvious effort put into building them seems disproportionate to the fractional productive land thus created.”50

These lines capture the capitalist view of farmers in modern Sana’a, one markedly removed to that of medieval Queen Awra who was mentioned earlier for strategically earmarking an year’s worth of state funds towards the repair of the terrace farms on the foothills of the basin.

The chewing of a narcotic stimulant plant called qat is a ~500 year old past-time in Yemen. While its addictive properties aren’t considered severe by the World Health Organisation, approximately 90% of men chew qat for hours every day and 50% of women use qat habitually.51 The main problem Yemen has with qat is its dire reductions to the country’s water and food stores.

In the following summary of the qat industry, it is the ‘cash economy’ which effects what crops are grown, and also how they are grown, which imparts negative effects on the population’s access to food and water. Lichtenthäeler claims that a shift towards growing qat in Yemen is not the only problematic shift in crops grown which is yet promoted by globalism and a cash economy, for example citrus and bananas are water intensive cash crops being grown instead of wheat. Still the reasons why and how qat is grown instead of food in a country which is failing to feed its people requires attention. As 90% of water use in the country is used for irrigation, and 37% of that share is for growing qat, an entire third of the available water in Yemen is used on qat.52 While the livestock industries (sheep, goats and camels) have increased steadily over the past decade, cereals (sorghum, wheat, maize, barley, millet) have declined a very serious 37% (total weight) in the years 2011-2016, partially due to the growth of qat.53 In considering that qat has a shelf life of no more than 48 hours it is also considered that road access to the increasingly centralised city is creating an allowance for such a water intensive crop to be grown out of balance with the needs of the people.54 Finally, the problem of growing qat and not food exacerbates itself, as the expensive equipment required to extract the water from the wells which are now up to an incredible 1,000 metres deep, extracting any water is only profitable if farmers are to grow the water intensive crop.55

It is apparent that, without the traditional social structure to govern farmers, they relish in the allowances made by trade reform, privatisation and centralisation by; growing the cash crop qat (not food), unsustainably hybridising new and old agricultural practices and modifying their land, all for the sake of capital. And yet the state whom introduced these allowances, is ineffective at managing the farmers, leading to an extreme over exploitation of the precious but diminishing food and water reserves in the region.

4.2: Case study 2: Hybrid urban lifestyles of 'old and new'

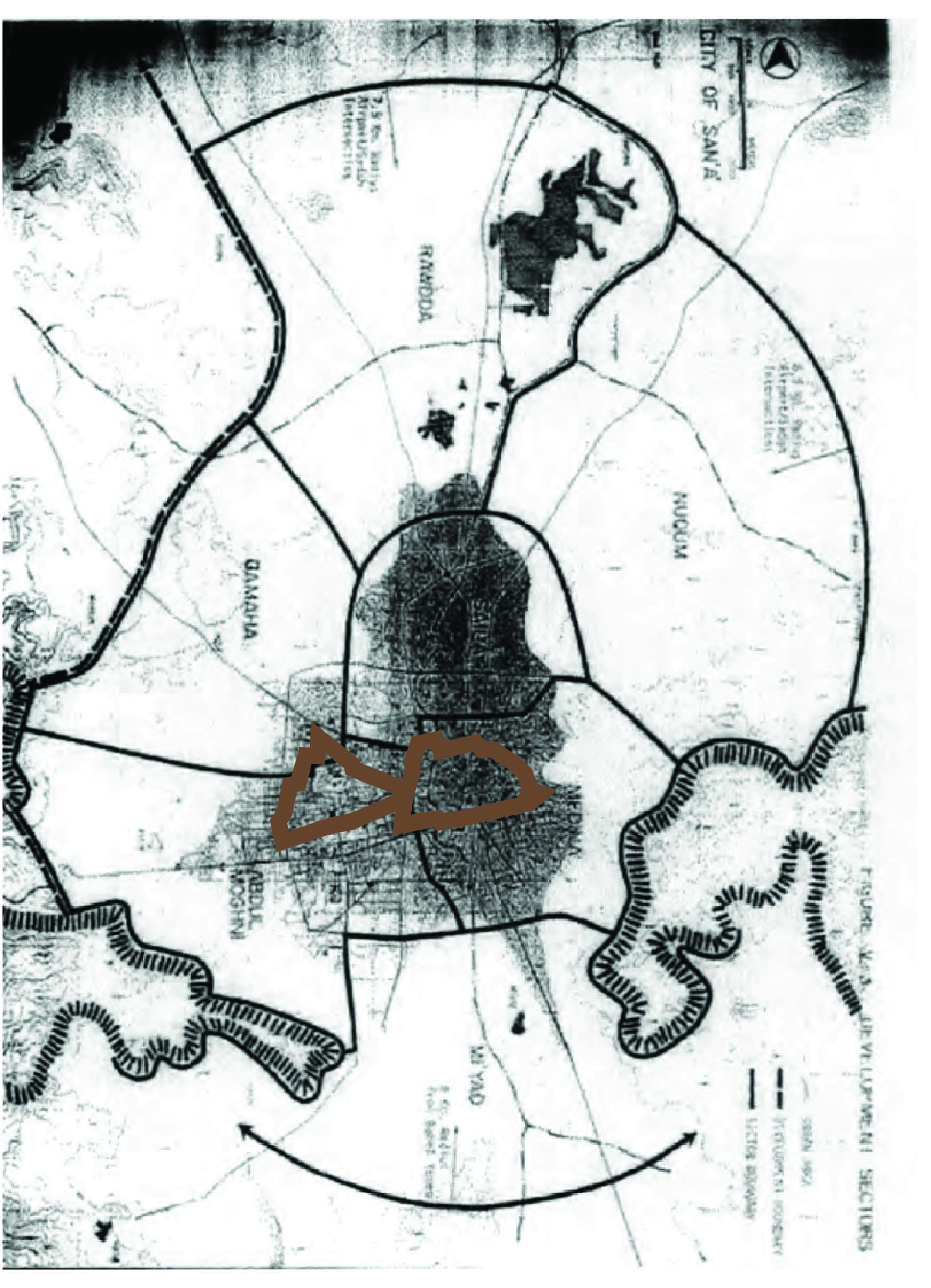

The historical iterations of the masterplan for Sana’a, namely the Egyptian Plans of around 1968 (refer to figure 13) and the Berger/Kampsax 1978 masterplan (refer to figure 14) anticipated the expansion of a new Sana’a as a sole objective, whereby site context such as agricultural functions and village relationships were barely considered but for their assimilation into a new civic system. In ignoring the existing context, ie the fabric of the villages and their cultural and geographical premises, these plans also rejected the historical knowledge of the landscape developed through the patterned nature of its long-evolved settlements. The masterplanners being from outside the region, and outside the continent for that matter probably contributed to this disregard of geographical context.56 This modern overhaul arguably has caused a negative change within the lifestyles of the Yemen people, whereby their traditional practices are hybridised by the pervasive modernity and globalisation of Sana’a. Though there are beneficial factors within these hybrid lifestyles of old and new, including the modern expectations of high living standards and better human rights, making it difficult to isolate modern overhauls as being ill-considered and superfluous aside from those born out of necessity. In this case study the masterplans for Sana’a are reasoned and yet proven as generators for the incohesive urban fabric and rampant centralisation of the region.

Vernanda’s doctoral thesis focused on the masterplanning of Sana’a is summarised here, with particular emphasis on the authorisers and long-term outcomes of such a plan. Prior to a recognised masterplan, the Ministry of Public Works had, upon the inception of the ministry in 1968, used a set of documents called the Egyptian Plans which in essence overlay a grid around the existing fabric of Sana’a and two other large towns in the region (refer to figure 13). In 1970, a physical planning division of the Ministry of Public Works became operational with the arrival of a United Nations Development Programme expert Alain Bertaud’ who was brought to Sana’a to establish the city’s first recognised masterplan, which was begun in 1971 to be fully implemented in 1978. This plan estimated the population of 1988 to be 280 000, about half of what would be the actual population in that year. Because of this gross underestimation, the city sprawled in an unpredictable way which the masterplanners predicted would be the case if no planning policies and planning infrastructures had been enacted. In 1980 experts from the German Volunteer Service were employed by the Ministry of Municipalities and Housing to decentralise the nation and bring regional townships to a modern standard,57 even this proved ineffective for the already overgrown city; Sana’a’s population exploded in this decade.

As described by Elsheshtawy previously quoted in this thesis, the absence of an adequate framework for development in the masterplans for Sana’a has created a disjointed urban fabric. This is further exacerbated by the ongoing use of the helplessly outdated masterplan of 1978, which failed to predict the immense and domineering population growth within the city.58 The placement of main roads determined by the 1978 masterplan radially emerged from the planned city’s centre just west of the Old City and just east of the historic Bir-al’Zab which once stood within the western ‘wing’ of the city’s walls. Despite this pattern’s intent to potentially decentralise the dense inner city,59 it inadvertently encouraged rural-urban migration from the outlying villages it connected to as well as facilitated the unplanned development of an in between zone, as evident in figure 15. The organisation of government buildings seem to follow similar disregard, adjacencies between ministries and other government organisations are inefficiently scattered,60 which perhaps contributed to, or partially resulted from the lack of cross-sectorial approaches (including the water sector) within the government which further exacerbated water mismanagement.61 These inefficiencies and inabilities were and still remain characteristics of an incompetent government wielding an incomplete and outdated plan, and so what had once been a rather successful decentralised pattern of development in Yemen has now been compromised by unguided modernisation and centralisation. In the case of the Old City, its functioning and traditional past-times were drowned by the confused modern city which effectively smothered it:

"(the Old City) has been flattered out and forced to express conditions of habitat and functioning leveled on those of the other city districts. The new urban form has been scattered to fragmented land use and to heterogeneous gated communities rather than homogenous communities within the old walled city gates."62

Eckert explains this kind of bipolar phenomena by making an example of a peculiar interaction between traditional relationships people have of the city’s marketplace while explaining the intricacies of these habits as changing due to inadvertent modernisation:

"The esplanade of bab al-Yaman outside the city walls, simultaneously an ‘urban port’ for the central souks, a working class central district and the city’s largest public transport terminus, appears as a huge central monopoly untempered by any outside pole of attraction, reflecting the rapidly growing city. Coaches, buses and taxis pour in from a wide area with no anchorage point. They come from gates that are constantly moving further out into the country and that have no concrete existence apart from the vegetable stalls that appear here and there on the pavements of the outer districts…

… We are forced to admit that everything that happens at Bab al-Yaman and in the souks, and that the large volume of vehicles and pedestrians is the most important quantitative and qualitative expression of this. The reason is that the city seems to be at the mercy of land speculation that both encourages and prevents the urbanization of specific areas and aims as much at housing as at rows of shops, which leads to movements outwards… They (Yemenis) only seem to feel comfortable doing their shopping and other business in the familiar universe of the souks (in the old city), and the prestigious urban souks at that."63

This is one example of how the historical city’s systemic functioning has been compromised, the souks (markets) of the Old City which retain their significance in a modern city do not maintain the sustainability of their traditional histories. The failed masterplan as allowing a problematic modern-traditional complex to occur is one example whereby efforts to accommodate for a larger population, provide modern services (namely water supply, sewerage, stormwater and sealed roads) for better living conditions, better accessibility, undertake heritage conservation and simply provide for oneself and one’s family, all have rippling effects away from the direction of their intended action. These inadvertent effects are channelled from one society’s hydro-interface with the Wadi al Sailah to another, and to another again. The snowballing of these uncoordinated effects of the disjointed societies within this city has contributed to its evermore failing management of flood, food and water. This phenomenon will be explored in the next three case studies.

Figure 13: ~1968 Egyptian Plans64

Figure 14: 1978 Masterplan by Berger / Kampsax65

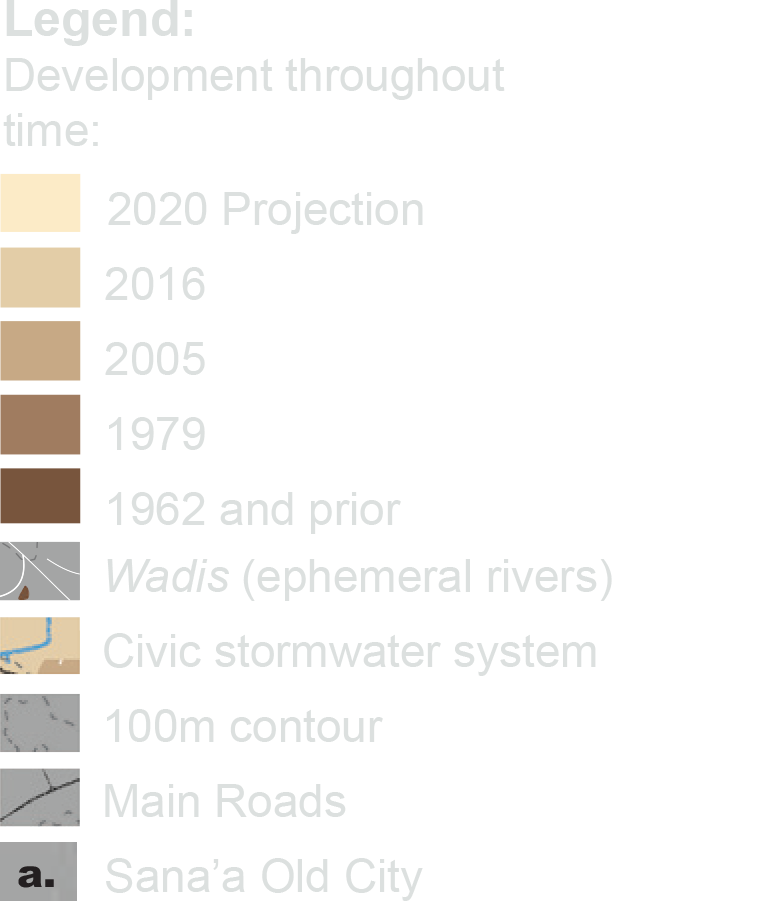

Figure 15: The growing development of modern Sana'a in the Sana'a Basin 66 - 5 000 grid

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Map description:

In the year 2005 the city began to reach its east-west limits as defined by Mt. Nuqum on the east and Mt. Ayban on the west.67 Exponential population growth, the tendency to construct lower density urban sprawl and the east-west borders of the plateau then accelerated development north and south. Currently the city limit spans from its centre approximately 35 kilometres to the north and 35 kilometres to the south along the Wadi al Sailah and its tributaries.68 Modern infrastructural interventions; the airport and the sewage plant make development further north (for those who can afford it) undesirable, and so the city is somewhat bounded from the north as well.69

Parti diagram 1:

Wadis are ephemeral rivers traditionally used as roads. To maintain the access to towns and areas in a modern world, roads are built alongside the wadis.

Parti diagram 2:

The Stormwater system makes a bridge out of the most developed parts of the city which floods travel under (to a certain extent). This cloister of stormwater infrastructure around the CBD and Old City chases the sprawling city’s extending arms of development north and south.

4.3 Case study 3: Shifting approaches to the conservation of the Wadi al Sailah

The shifting and contradicting recommendations of UNESCO for the conservation of the Wadi al Sailah is an example on how one of many organisations had attempted to rein the negative effects of population growth on the Old City’s traditional functioning. The differences between two advisory texts from 1986 and 1992 are of dramatic contrast — one before the population boom had truly began and one after have seemingly contradictory recommendations

Yemeni people have traditionally used wadis for roads as they lead to villages and contain the most accessible groundwater and are therefore spotted with an abundance of wells.70 However, people would have traditionally entered through the city’s main gates; Bab al’Yaman to the south and Bab Sha’ub to the north, not its Khandadiq (floodgates) which are along the wadi bed. With the introduction of the car which cannot traverse the tight-knit streets of the Old City, the Wadi al Sailah became a central component of access to the internal souks of the historic urban fabric,71 though Ali Abdul Moghri Street (which bordered the since removed wall of the Old City) would and still does most prominent thoroughfare (refer figure 7 and 16). Still, because of the ongoing densification in between the Old City and Bir-al’Zab, characterised by several impermeable public squares and government complexes, the Wadi al Sailah has eventually become yet another thoroughfare. Discussion on infrastructural interventions to improve the Wadi al Sailah had been conferred by designers and policy makers since the 1970s, though modern interventions began only in 1987 - the modest conservation endeavour to restore mud walls and banks which protect the Old City from monsoons.72 Its 1994 urban transformation into a paved and depressed four lane highway73 was warned against by renown urban conservationist architect Ronald Lewcock just 8 years before in 1986:

“A particular danger that has to be avoided is the cutting through of a main road across the “Old City” from north to south; this has already been proposed above a covered-over sa’ilah (dry riverbed) where the flood waters run. Its effect would be catastrophic, irrevocably dividing the traditional way of life of the people of the “Old City” into two weaker, fragmented zones, and inevitably attracting high commercial buildings on either side of it. From the viewpoint of conservation it would introduce alien features of such a scale and impact that the conservation of the western half of the “Old City” - and therefore ultimately of the whole - would become meaningless.”74

In an interesting contradiction to Lewcock’s recommendation, six years later, Eckert (another conservationist of heritage environments who works with UNESCO) describes the prospect of roadway-canalisation within the Old City as a “reality that needs to be brought under control”75 listing the benefits of such an intervention:

...Reinforcing its fragile banks would make it possible to reconcile the natural function of draining occasional rain and flood waters with the specific function of “draining off” vehicles entering the road system within the walls, in such a way as to also preserve the supplementary functions of Wadi Saila; A ‘rampart’ just behind Bab as-Sabah, a car access via the Harat al-Qasimi ramp, landscaping: an urban riverside and a mirror image of the Medina all along the bank.76

Arguably, the difference between Lewcock’s and Eckert’s recommendations perhaps lie in the distinction between the road’s prospective functions of protected and maintained access to the Old City versus that of the road as becoming thoroughfare. While UNESCO was involved in developing traffic plans for the Wadi al Sailah (despite them only being implemented in 2004),77 neither Lewcock nor Eckert made such considerations or technical distinctions in the texts cited. Also contradictory to Lewcock’s concerns of the city being divided, Eckert later claims that the connection from east to the west by the proposed introduction of several footbridges (which would eventually be built regardless) would do harm to the surrounding areas:

“(it would) threaten the tranquility of one of the finest residential sectors of Old Sana’a. The quiet and privacy of this attractive district, apparent in its gardens and small squares, would suffer greatly from this (pedestrian traffic).”78

Essentially, both scholars had concerns regarding interruptions to the ancient urban fabric and the traditional societal networks of the areas around the Wadi al Sailah. In 1986 Lewcock predicted the formalising of Wadi al Sailah into a major paved road would have divided the traditional relationships between people either side of the wadi, while in 1992, Eckert claimed that due to the intense civic commute from the region into the Old City constructing a road would have at least taken pressure off the city’s gates (namely Bal al’Yaman) and aided the functioning of the adjacent souks. Eckert went on to claim that connecting each riparian edge of the wadi with footbridges, a solution which at face value seems to facilitate the urban relationships Lewcock claimed would be otherwise lost due to the wadi’s canalisation, would have in fact destroyed the urban fabric of the surrounding areas. Eckert’s reasoning was that due to the densification of the new city centre between Bir-al’Zab and the Old City, the wadi-canal-road without footbridges was acting as a buffer from those who would otherwise trek through the Old City’s neighbourhoods to the central souks.79 The shifting approaches towards conservation by UNESCO advisors owe their contradictions to a small window of time, characterised by an unfathomable rate of change in population growth (see figure 5 and 17). The changing opinions of professionals in the field of conservation not only iterate the complexities of a rapidly changing Sana’a but also the difficulties of exercising solutions in a region where societies are both communicatively and cooperatively severed from one another and yet influentially connected.

The canalisation of the Wadi al Sailah into a four-lane thoroughfare and the construction of five additional footbridges over it were both undertaken in 1994 despite Lewcock’s and Eckert’s recommendations.80 Both scholars were also correct in their concerns that such infrastructures would cause negative effects on the Old City. Michele Lakrambos describes the residents’ distaste in cookie-cutter modernist/globalist typologies being constructed on the Old City’s new popularised esplanade:

“Residents of the “Old City” and others protested against construction of the theatre-arguing that the use of waqf property for entertainment went against the original intention of the patron (waqif). Moreover, the garden was attached to a mosque: entertainment and music were not appropriate for this site. The controversy was covered in the press, and provoked a debate in Parliament. On my rounds with inspectors, we were approached by a young man who demanded to know why GOPHCY (General Organisation for the Preservation of Historic Cities of Yemen) was not discussing the matter. Any modernization (istihdath) on the “Old City” of Sana’a is forbidden,” he said. “It says so on the Internet” (i.e., on UNESCO’s website). According to a GOPHCY official, residents found UNESCO’s proposal of a public garden more appealing, and more compatible with the waqif’s intentions. In their effort to preserve these intentions-and, implicitly, to resist the coopting of their city by an elite and alien program-residents invoked the authority of UNESCO alongside Islamic Law. During the months of Ramadan that year, in what may have been an effort to appease residents, the theatre was used for performances of religious music *tawshih) by groups of from different parts of Yemen.”81

The civic access of a main arterial road coupled with the globalist gentrification of its esplanade has placed an untraditional and unprecedented importance on the adjacent districts, eroding their urban performance and heritage values. In a specific case modern infrastructures have begun to transform the towerhouses on the eastern esplanade, these modern infrastructures are; footbridge connections leading to the relatively new city centre, the growing area of carparks (which presumably service the central souks as described by Eckert) and the latter being facilitated by the adjacent vehicle ramps to the Wadi al Sailah. A meaningful correlation can be made between; aerial photography from 2004-2016, maps which define the towerhouses’ ground-floor programs and a map depicting the occurrence of recent renovations and refurbishments of these towerhouses. With this data it can be recognised that there is a trend in refurbishments and renovations to accommodate retail and service programs which cloister new carparks.82 Additionally, the creation of impermeable surfaces through canalisation and carparks has reduced the groundwater permeation (refer figure 21), further contributing to the reduction of the groundwater aquifer and the unviability of traditional agricultural practices of the vernacular urban environment, this phenomenon will be described in detail in the following case study.

Figure 16: Road use map83

Figure 17: Timeline of conservation of and around the Wadi al Sailah84 - click photo to enlarge

Figures 18 and 19: Section across and elevation along the Wadi al Sailah85 86

Legend:

a. Sloped canal wall (~40 degree inclination). The gentle stone paved sections of the Wadi al Sailah are designed to be traversable.

b. Road into Old City

c. Esplanade planter

d. Towerhouse

e. Esplanade storefront

f. Inaccessible towerhouse. Due to the tiered urbanity throughout the city and the risk of flood from the Wadi al Sailah, many towerhouses do not address the esplanade. The higher internal floor leads means the esplanade is edged with a stone wall in this case.

g. Carpark. There are many carparks around the Wadi al Sailah road/canal as the Old City is barely traversable by car.

h. Terraced esplanade.

i. Many courtyards partly compose the esplanade to the Wadi al Sailah. They feature ornate stone details and maintained display gardens.

j. Wadi al Sailah road is approximately 10m wide throughout the Old City. This is a tight 4 lane highway. The profile of the road means it can function when carrying small amounts of stormwater.

k. Bus stop on the edge of the sloped canal wall.

l. Brick course work about 300mm high designed in a pattern to allow water to permeate through. Terraced threshold up to storefront are often ~ 400mm high.

n. During times of little rainfall, the profile of the road forms large gutters at its edge.

o. The typical flood of the Wadi al Sailah forbids its use as a road.

p. Diagrammatic representation of 2008 floods where floodwater covered the esplanade and rose up the high thresholds of the nearby buildings.

q. The flood of 878 / 879 AD flooded The Great Mosque. As this was after the fortification was constructed diverting the Mount Nuqum flood course it is assumed that this flood came from the Wadi al Sailah. The level depicted is about 1.5 metres above the floor of The Great Mosque several hundred metres upstream and 15 metres higher in elevation. This flood event may be nothing more than a legend.

Figure 20: Water and flood systems/conditions of the Old City87

Note: This map is based off the area around Maqashama Al-Kharaaz and Al-Jala’a however some building typologies and wadi-city interfaces have been introduced to complete the catalogue. Considerable accuracy in the representation of urbanities, water related typologies and their spatial relationships has been retained.

Figure 21: Water table height, depths of wells and their distance from the Wadi al Sailah throughout time - 20m grid 88

Figure description:

This section diagram depicts the falling groundwater levels around the Wadi al Sailah. Evidently, after the canalisation of the wadi in 1994 and the massive population increase since the late 1980s the groundwater table has dropped considerably. In both post-canalisation dates 2002 and 2007, the three wells closest to the wadi appear most affected. The lines representing the well depths continue past the groundwater table indicating their changing depths throughout time.

4.4: Case Study 4: The atomistic modern development and its contributions to water mismanagement

The conversion of the Wadi al Sailah from a broad floodplain to a thin paved canal has expanded over the past two and a half decades to accommodate ongoing developments that radiate outward from the city’s centre and the Old City (refer figure 22).89 Naturally the wadi is a wide floodplain in which floodwater flows through in braids. While usually empty, the amount of rain focused from the basin to this one river means that it fills quickly but also permeates below the surface of the alluvial ground quickly. Historically the water table was as little as 5m under the ground’s surface, and therefore very easily accessible by hand dug wells.90 As mentioned, traditionally, and as is in the case of the Old City, flood resilient housing with a sacrificial ground floor made of baked brick, surrounded by agriculture,91 and patterned systems of dykes, wells and small canals were manifestations of the Yemenis’ harmony with their geographies. Bank-to-bank canalisation of large sections of the Wadi al Sailah inverts this vernacular harmony with riparian landscapes into a modern infrastructure expressing its wariness of inevitable flooding. In modern Sana’a, the wadi is reduced to a paved canal cut into the earth so that building typologies of modern architecture may occupy what was once a broad wadi bed. This densification of the wadi’s floodplains is also greatly catalysed by the conversion of the canal to a four-lane highway, again an urban form quite the contrary to vernacular developments which kept the wadi bed as an agricultural land for the most part. The increasing development which precariously lines the esplanade of the Wadi al Sailah in the modern city also calls for further canalisation. This case study examines how this cycle of canalisation and development can contribute to both flood and drought.

In the denser areas of the city with an appraised road network,92 large buildings and extensive paving line the otherwise permeable alluvial soil underneath, further increasing the necessity to quickly flush flood water where it would otherwise linger and damage property or interrupt the city’s functioning. Despite the canalisation and its tributary stormwater system, the Wadi al Sailah does still flood considerably beyond its banks. These floods interrupt traffic and damage the properties on the Wadi al Sailah’s immediate floodplain, as mapped by Pakakos and Root in their one-in-one-hundred-year flood scenario calculations (see figure 22).93 The impermeable surfaces of the modern city exacerbate these disasters. Figuratively, the equation of ‘whether to build’ is answered by a balance of two variables - land value (as influenced by availability, roads/traffic, and broader market trends) versus flood risk. What complicates this is the acknowledgment that these trending developments themselves generally increase flood risk.

The flushing of water from the city’s impermeable surfaces downstream is a contributor to the region’s rapidly depleting underground alluvial aquifer. Urbanisation can either increase the groundwater permeability or decrease it depending on the services of the city and the types of soil which the city was originally founded upon. Given that the soil is alluvial silts composed of sandstone and volcanic rock, it is assumed that the groundwater permeability of the soil under Sana’a would be relatively higher than average, and given that modern sewer systems and stormwater infrastructure in modern developments are relatively extensive, it could be assumed that ground permeability is relatively less than in the areas of informal developments,94 as the latter isn’t lined with paved roads/sidewalks nor is it serviced by water supply/stormwater/sewerage infrastructure. Therefore it would be likely, and as supported by investigations into the groundwater depth around wells throughout the Old City near and far from the Wadi al Sailah (refer to figure 20), that the canalisation of the Wadi al Sailah, and other stormwater and sewerage services have decreased groundwater permeability in Sana’a, contributing to falling groundwater levels.

It must be mentioned that when considering the average groundwater levels for the entire basin, water drawn from the aquifers is almost as much as the water recharging the aquifers,95 the problem is rather the city’s unsustainable interventions spatially shift the distribution of groundwater, meaning that some aquifers run out of water as the groundwater above them is carried through stormwater infrastructure to other areas and flooding them. It is evident by this and other examples that the city’s systematic failure to store water and mitigate floods is therefore defined as the spatial imbalance of water throughout the region. It is indeed the disjointed hydro-interfaces of Sana’a which create this problem. This is a stark contrast to the aggregated water management systems of pre-modern Sana’a as depicted in figure 9.1 and 21, whereby the urban environment (ie the buildings and the water infrastructure) allowed and relied upon the natural distribution of floodwater and aquifer recharge.

Figure 22: Development as a response to and a premise for canalisation96

}

Map Description:

The pressure built from the city’s limits (mountains, airport and wastewater treatment facility) result in the inward compression against the most flood prone lands of the Wadi al Sailah floodplain. In the centre of the modern city (segment 5), the threshold between development and the

wadi

has been reduced to a retaining wall and a street, interfaced by tall structures which look over the wadi, several kilometres north, the city begins to open up to agricultural programs which interject between the

wadi

and modern development, this reduced pressure to develop thankfully leaves the traditional fabric of the historic settlement Al-Rawdah largely intact. Evident in segments 1 and 2 is the airport and the wastewater trench. Here, dense informal developments disperse into small albeit growing clusters girt by large expansive farmland. Unlike the pressurised modern city, the farms along the

wadi

bed to the north promote groundwater permeation instead of flushing water downstream.

4.5: Case Study 5: Informal developments on the Wadi al Sailah.

Informal developments emerge as proof of polarisation between an arrested, insufficient state and a resistant, resilient traditional population. More specifically, the genesis of informal developments and their ongoing development is the product of the clash between the traditional lifestyles of the people and the arrested state which fails to control its assets or provide an adequate framework for development. The effect is very significant with approximately 16.5 - 20.5% of Sana’a’s population residing in informal developments.97 Hema Al’ Matar, the third largest of the informal developments in Sana’a which houses 27 000 people (as of 2008), is located at the northern mouth of the canal on Wadi al Sailah as the plume of development visible in figure 22. Development further north in segments 1 and 2 (figure 22) do not appear formal either, though they aren’t recognised as Hema Al’ Matar by Shorbagi.98 Emerging around 1990, Hema Al’ Matar has manipulated the Wadi al Sailah bed with an organic arrangement of housing and extensive farmland.99 This development and other informal developments in the region haven’t earned their legitimacy, the state not only intervenes with infrastructural interventions but also seeks to relocate these people. While concerns of the inhabitants living conditions and safety are legitimate, other agendas of corrupt state officials have also been documented.100

Despite its intentions, the state is generally inefficient at providing alternatives or even haltering the ongoing illegal sale of land in these informal developments. Shorbagi describes how an arrested and inefficient state facilitates farmers’ illegitimate claims to land which can then be sold illegally to those looking to build a home:

“The state has no exact inventory of its own land which facilitates encroachment by private persons, particularly on the slopes adjacent to agricultural land 20% of which can be legally claimed by private land owners to protect their water resources. However, private land owners often occupy much larger land parcels and tend to claim non-agricultural land as agricultural land to support their claims of ownership. In practice, it is the State that has to prove ownership in case of first registrations without knowing the exact boundaries of public land which opens the door for all sorts of manipulations. Therefore, land is in most cases traded informally with the use of written documents (basa’ir) that are certified by the amin al-mantiqa, a government appointed area chief.”101

Obviously these developments would not have been planned in the 1978 masterplan, and in most cases are illegal encroachments on prohibited land. In the case of Hema Al’ Matar, this development prohibition is based on a few reasons, foremost being the state’s security and safety concerns regarding the nearby airport. While claimed to be not as important of a problem to the state, part of this land along the Wadi al Sailah is also zoned as “saila” which the government claims are floodplains unfit for development.102 The nearby sewage plant is another reason for the lack of official development in this area prior to 1990 when the settlement first emerged.103 The Food and Agriculture Organisation stresses that the agricultural use of the wastewater trench which trails approximately thirty kilometres from the partially-functioning treatment plant along the Wadi al Sailah is a "serious health concern".104 Despite this, water from the wastewater trench as well as natural floodwater is used for farming the surrounding wadi bed, just the area would have been like in pre-modern times.

Modern interventions seeking to rightfully improve poor living conditions in informal developments cause inadvertent problems in the urban fabric of these quasi-vernacular developments. Reported in interviews with residents of a different informal development, Mahwar Aser, the construction of schools, road paving, sewers, health centres and other vital infrastructure has been funded by the World Bank.105 While Hema ‘Al Matar has not been as significantly canalised (deepened or paved) in comparison to the Old City and the modern city, the introduction of bitumen roads either side of the Wadi al Sailah rise above a depressed floodway for a length of 1,200 metres within the informal development.106 This work was presumably undertaken by the state and perhaps funded by the World Bank as was the case in other informal developments. The rigid structure of these sealed roads protect the wadi banks from erosion, and therefore protect the poorly built masonry buildings on these banks.107 However this canalisation also compromises the surrounding wadi bed’s use as an agricultural plain by concentrating floodwater to a singular canal, denying the spilling of floodwater to the broader floodplain and spate-canals, as well as simply reducing the amount of land which can be farmed in the wadi bed. Roads on the riparian edge provide access to floodplains of now defunct agricultural land, and so they are sold off for development. Also evident as in the other areas of the city already discussed, the phenomenon of the wadi becoming a road promotes development precariously close to the floodplain.108

This analysis of the complex relationships between state infrastructure and informal developments reveals the many interwoven chains of influence and their varied mediums. In the case of Hemar Al’ Matar, the construction of a road influences land titles which in turn influence informal development patterns; these informal development patterns also draw other civic influences such as the economy of the airport, and canalisation of the wadi which leads to extensive development on a floodplain (refer to figure 23 and 24). Rather than these people being integrated into a broader holistic system or harmoniously integrating modernist interventions into their hydro-interface/urban fabric, they are internally conflicted and externally ill-considered, if at all, negatively affecting the livelihoods of the inhabitants while propelling their population growth.

Figure 23: Farming plots as generators for patterns of informal development109

Map description:

In Hema Al Matar, the farms’ relationship with the Wadi al Sailah is also a premise for its ongoing pattern of development (not just its genesis). Land tenure is a key influencer of informal development as evident in the analysis of pre-existing farming plots and the developments which are built on them between 2004 and 2016. The aggregated clustering of buildings and their joined cloistering forms in the informal developments in and around Sana’a are reminiscent of the pre-modern vernacular settlements of the region, insinuating a similar geographical and social premise to pre-modern villages.

Figure 24: Patterns of informal development110

Map callouts:

a. Figurative path of the Wadi al Sailah prior to the construction of the city’s wastewater treatment plant as evident by the river’s path to the north and south of this infrastructure.

b. Development encroaching on the wadi is also seen just to the south of this point while development which relies on an upstream premise can be seen in the developments on the far north of the figure.

c. Canalisation goes back 1,200 metres from this point.

d. Recent development of an area which would experience considerable velocity flood water coming from around the bend. Its development is encouraged by the canal/road infrastructure.

e. Houses removed from wadi due to slip-road canalisation.

Map description:

It has been demonstrated that as people settle large plots of agricultural land with the aims of wadi access and road access, properties are divided in thin bands between and perpendicular to the wadi and the road. This confines informal development to a similar pattern when particular land-owners informally subdivide their land. This causes the ongoing growth of informal developments to eventually interface and interrupt the wadi, changing its course and the surrounding landscape profoundly.111 Additionally, Shorbagi states that prospective residents of informal developments avoid authorities during the construction of these developments, by initially screening views from the road with development, growth behind and towards the wadi is less visible and perhaps less likely to draw attention.112

As the development reaches out onto the wadi, flood waters are slowed downstream, causing sediment to settle which further directs the path of the wadi away from these areas which are then developed. This pattern repeats spatially throughout the informal development, compounding over the years studied.

5.0 Summarising the phenomena of atomistic societies’ water mismanagement and the ramifications

Through the lens of water mismanagement the effects of the Sana’a Basin’s societal disharmony and their subsequent atomisation has been measured, both as a catalogue of effects and the statistical inclusion of the magnitude of these effects. The schism pivoting on the 1962 revolution whereby rapid globalisation, modernisation and subsequent centralisation has fractured the societal hierarchies and practices of the once sustainably inhabited region. Now, Sana’a is completely absenting of any cohesive and wholistic water management strategy. While the society’s atomisation today ensures a non-holistic approach to water management, these self-segregating ‘atom societies’ are also internally polarised via the influence of globalisation, modernisation and centralisation against their traditional vernacular practices (whether they be agricultural, development, trade, water usage and/or governance). This isn’t just allowed by the disharmonic nature of the societies but also owing to the political whims the modern state which in its arrested form, predictably fails to set up successful and resilient frameworks (whether they be planning, policy, enforcement, or funding), and in turn allowing the further atomisation of Yemen society.

Water is one element despite its varying roles as an asset, a resource, a human requirement, a danger, a landform and flood. The appreciation of this wholism of water provides an invaluable context marking the division between societies who respond and interact differently towards the roles which water plays. The consequences of these divisions are dire, given that as of 2016 90% of food in Yemen is now imported,113 and even more catastrophic is John Sharp’s prediction that if no such action is taken the aquifers under the city of Sana’a may become dry as soon as 2017.114 The flooding of the city doesn’t just damage buildings and interrupt the city’s functioning, it also causes fatalities which are reported by various media sources almost every year. The success of solutions for Sana’a’ and broader Yemen’s dire water management problems pivot on the acknowledgment and subsequent reconciliation of its societal problems including their fractured and fragmented developments and infrastructures, which create their entangled struggle for water access, food production and flood mitigation.

87. Fadhl Ali Saleh Al-Nozaily et al., Promotion of indigenous knowledge in water demand management for the historical Old Sana’a City’s Gardens (Maqashim), (Sana’a: The Water and Environment Centre (WEC), Sana’a University, 2015). By author using this resource. 1. The Guardian, “Water scarecity in Yemen, the country’s forgotten conflict” news release, April 2, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2015/apr/02/water-scarcity-yemen-conflict.

2. Craig Giesecke, Yemen’s Water Crisis: Review of Backgrounds and Potential Solutions, (USA: Bridgeborn, Inc. and Library Associates, 2012).

3. Time Magazine, “Is Yemen Chewing Itself to Death?” news release, August 25, 2009, http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1917685,00.html.

4. “Google Earth,” Google, 2017, https://www.google.com.au/maps/. By author using these resources.

5. By author.

6. Yasser Elsheshtawy, Planning Middle Eastern Cities: An urban kaleidoscope in a globalizing world, (London: Routledge, 2004), 96.

7. “Google Earth,” Google, 2017, https://www.google.com.au/maps/. Pre-modern developments were generally identifiable as those vernacular urban arrangements that are not listed as informal developments. By author using these resources. Wadis were based on google maps and other hydrological study cited.

8. Center for Planning and Architectural Studies; Center for Revival of Islamic Architectural Heritage, Principles of architectural design and urban planning during different Islamic eras (Saudi Arabia: Organization of Islamic Capitals and Cities, 1992).

9. Ibid., “Google Earth,” Google, 2017, https://www.google.com.au/maps/.

10. R B Serjeant and Ronald Lewcock, Sana’a: An Arabian Islamic City (London: The World of Islam Festival Trust, 1983), 132.

11. R B Serjeant and Ronald Lewcock, Sana’a: An Arabian Islamic City (London: The World of Islam Festival Trust, 1983), World Bank, Population of Yemen, 1994 census, accessed June 19, 2017, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/910671468345864207/pdf/YEMEN1IUDP0PID0Concept0Stage005128-08.pdf, “Population of Yemen, 1994 census”, Bab-al, n.d, http://al-bab.com/population-yemen-1994-census.

12. By author.

13. Aḥmad B. ʿUmar al-Zaylaʿī, “Towards a new theory: the state of Banī Mahdī, the fourth imamate in Yemen,” Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 37 (2007), Z. al-Abdin,”The Free Yemeni Movement (1940-48) and Its Ideas on Reform” Middle Eastern Studies 15, No. 1 (1979), R B Serjeant and Ronald Lewcock, Sana’a: An Arabian Islamic City (London: The World of Islam Festival Trust, 1983), Ronald Lewcock, The Old Walled City of Sana’a (Paris: UNESCO, 1986), SBS, “Yemen cholera cases could hit 300 000”, news release, May 19, 2017, http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/2017/05/19/yemen-cholera-cases-could-hit-300000, Veranda, Fernando, “Tradition and change in the built space of Yemen: The description of a process as observed in the former Yemen Arab Republic between 1970 and 1990”, (PhD Thesis, Durham University, 1994), Yemen Times, “Sana’a Then and Now,” news release, 6th January 2015, http://www.yementimes.com/en/1848/photoessay/4772/Sana%E2%80%99a-Then-and-Now.htm, Howard Humphreys & Sons, “Wadi Saila Proposed Improvements” (Yemen Arab Republic: Yemen Arab Republic, n.d.), “Population of Yemen, 1994 census”, Bab-al, http://al-bab.com/population-yemen-1994-census. By author using these sources.